From the Archives: Naming and Confronting Anti-Muslim Violence in Canada

January 29, 2025

On January 29, 2017, six worshippers were killed in an act of white supremacist violence at the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec City. Many others were injured. Today, honouring the lives of Ibrahima Barry, Mamadou Tanou Barry, Khaled Belkacemi, Abdelkrim Hassane, Azzedine Soufiane, and Aboubaker Thabti, we mark the National Day of Remembrance of the Quebec City Mosque Attack and Action Against Islamophobia. As we remember, we look to the Muslims in Canada Archives (MiCA) collections to trace the ways that Muslims have been naming and confronting anti-Muslim violence in Canada. We invite you to explore these materials, reflect on the historical present and consider the role of archives in practicing justice.

While Muslims in Canada have long navigated discrimination both as individual acts of hate and, importantly, as systemic barriers to rights, ‘Islamophobia’ was not commonly used to describe these experiences until the late 1990s. The term was, in part, popularized with the launch of a 1997 report on Islamophobia published by the Commission on British Muslims. The report took focus on Muslim communities in the United Kingdom – offering sixty recommendations targeted at government departments and local/regional bodies – however it generated interest globally. In Canada, anticipation for this report is referred to in the October/November 1997 issue of Muslim Word, a community publication out of Scarborough, ON. Without naming Islamophobia, the February 1997 issue of Muslim Word draws readers attention to violence against Muslims at two different fronts: at the hands of Canadian Armed Forces in Somalia and up against a racist mob of students in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Read side by side, these stories signal to the ways that, for many Muslims living in Canada, the colonial wars, imperial extraction, racist encounters, and state violence are experienced in intersecting ways, bleeding and blending into one another.

Without naming Islamophobia, the February 1997 issue of Muslim Word draws readers attention to violence against Muslims at two different fronts: at the hands of Canadian Armed Forces in Somalia and up against a racist mob of students in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Read side by side, these stories signal to the ways that, for many Muslims living in Canada, the colonial wars, imperial extraction, racist encounters, and state violence are experienced in intersecting ways, bleeding and blending into one another.  Anti-Muslim sentiments are also felt and named in the December/January 1998 issue of Muslim Word wherein the role of Canada’s spy agency, CSIS, is scrutinized for “treading on [Canada’s] democratic values” and working with “Muslim-bashing” and “pro-Israel” collaborators. More specifically, the article traces the impact of ‘terrorist’ designations on Muslim fundraising activities such as humanitarian operations in the Muslim world. The article includes a discussion on the targeting of anti-apartheid and peace activists, illustrating a long pattern of anti-Palestinian racism that overlaps, and in some instances undergirds, experiences with Islamophobia. In response, writer and lawyer Faisal Kutty suggests these targeted groups including “Muslims, Arabs, Tamils, and Sikhs should have major input” in legislations relating to national security.

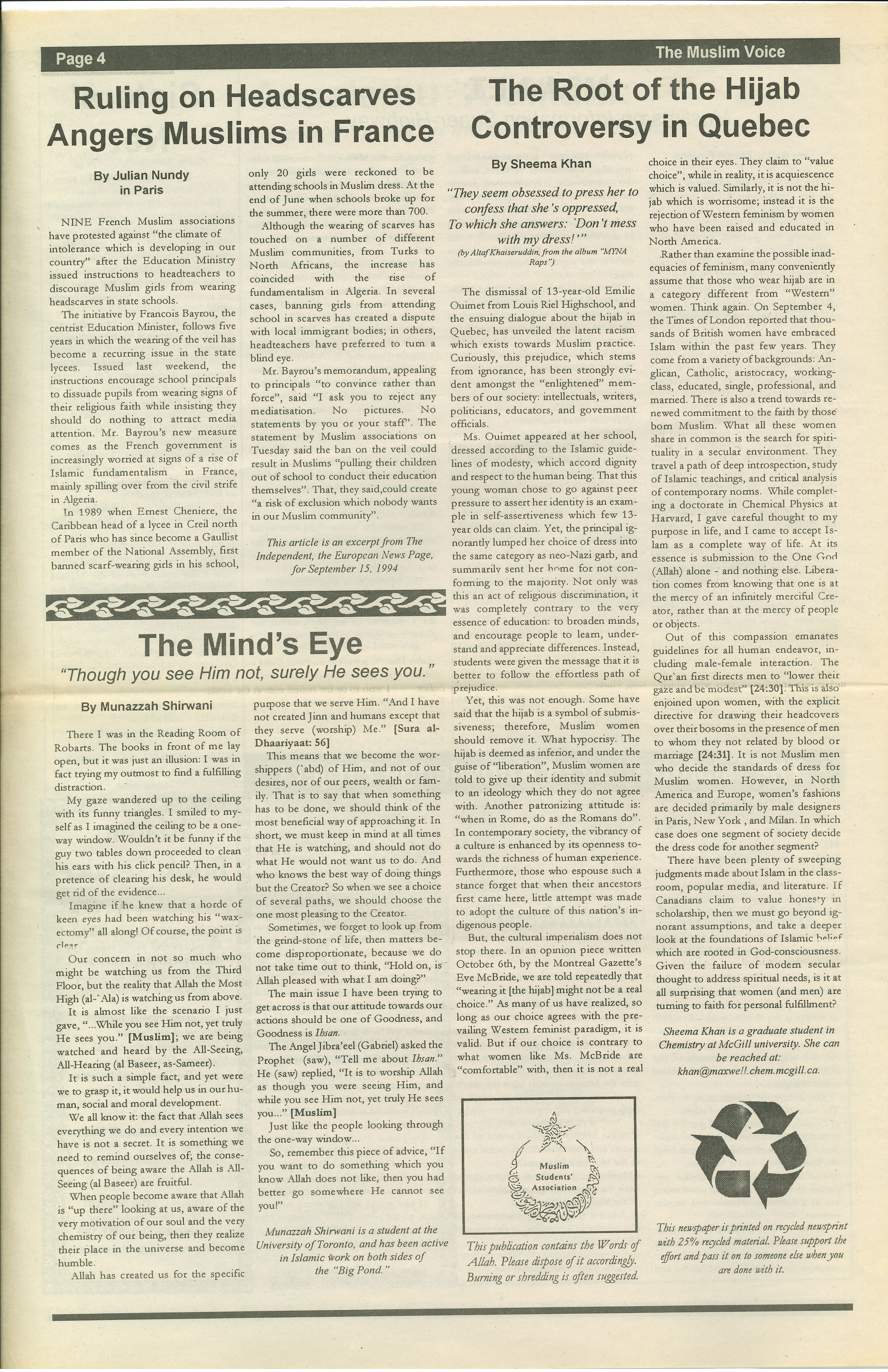

Anti-Muslim sentiments are also felt and named in the December/January 1998 issue of Muslim Word wherein the role of Canada’s spy agency, CSIS, is scrutinized for “treading on [Canada’s] democratic values” and working with “Muslim-bashing” and “pro-Israel” collaborators. More specifically, the article traces the impact of ‘terrorist’ designations on Muslim fundraising activities such as humanitarian operations in the Muslim world. The article includes a discussion on the targeting of anti-apartheid and peace activists, illustrating a long pattern of anti-Palestinian racism that overlaps, and in some instances undergirds, experiences with Islamophobia. In response, writer and lawyer Faisal Kutty suggests these targeted groups including “Muslims, Arabs, Tamils, and Sikhs should have major input” in legislations relating to national security. Articles in The Muslim Voice, a publication by the University of Toronto Muslims Students’ Association, point to the ways that students were attuning to anti-Muslim violence at home and abroad: in Quebec, in France, and in the US. While oftentimes framed as individual acts of hate and racial discrimination, the systemic nature of Islamophobia – and its impacts on Muslim life – are taken up in “The Root of Hijab Controversy in Quebec”. The article from 1994 describes latent racism in Quebec as tied to a broader cultural imperialism that particularly targets Muslim women. Other student articles discuss the proposed hijab ban in French public schools and the desecration of “another” mosque in the US.

Articles in The Muslim Voice, a publication by the University of Toronto Muslims Students’ Association, point to the ways that students were attuning to anti-Muslim violence at home and abroad: in Quebec, in France, and in the US. While oftentimes framed as individual acts of hate and racial discrimination, the systemic nature of Islamophobia – and its impacts on Muslim life – are taken up in “The Root of Hijab Controversy in Quebec”. The article from 1994 describes latent racism in Quebec as tied to a broader cultural imperialism that particularly targets Muslim women. Other student articles discuss the proposed hijab ban in French public schools and the desecration of “another” mosque in the US.

Looking to the archives, experiences with anti-Muslim violence are oftentimes described by Muslims as a threat to their safety and an erosion of constitutionally guaranteed rights in Canada. We also see the ways that Muslims confront this violence through writing and action. For example, in August 1985, the Canadian Society of Muslims published Eclipse of the Sun: Bigotry Obscures Objectivity, a bulletin tracing the Toronto Sun’s patterns of prejudice against Muslims. The publication directly responded to five Toronto Sun articles that were illustrative of general trends of hate literature.

Looking to the archives, experiences with anti-Muslim violence are oftentimes described by Muslims as a threat to their safety and an erosion of constitutionally guaranteed rights in Canada. We also see the ways that Muslims confront this violence through writing and action. For example, in August 1985, the Canadian Society of Muslims published Eclipse of the Sun: Bigotry Obscures Objectivity, a bulletin tracing the Toronto Sun’s patterns of prejudice against Muslims. The publication directly responded to five Toronto Sun articles that were illustrative of general trends of hate literature.  Similarly, in 1997-1998, the Canadian Islamic Congress (CIC) published a case study on “Anti-Islam in the Media”. The study questioned if Canadian media including the Globe & Mail and the Toronto Star were adhering to professional standards with regards to their coverage of Muslims. The findings highlighted articles that labelled Muslims as ‘terrorist’ and ‘other’. The CIC named the implications of this labelling — threats to the safety of Muslim children and families. The study identified the most anti-Muslim coverage in the reporting of international news, making direct connections between this discrimination and imperial investments in the Global South: “interests in oil, strategic location and as a consumer market for their manufactured products”. The study also invited journalists to seek the input of Muslim community leaders.

Similarly, in 1997-1998, the Canadian Islamic Congress (CIC) published a case study on “Anti-Islam in the Media”. The study questioned if Canadian media including the Globe & Mail and the Toronto Star were adhering to professional standards with regards to their coverage of Muslims. The findings highlighted articles that labelled Muslims as ‘terrorist’ and ‘other’. The CIC named the implications of this labelling — threats to the safety of Muslim children and families. The study identified the most anti-Muslim coverage in the reporting of international news, making direct connections between this discrimination and imperial investments in the Global South: “interests in oil, strategic location and as a consumer market for their manufactured products”. The study also invited journalists to seek the input of Muslim community leaders.  Reflecting on systemic Islamophobia, Syed Adnan Hussain contends that an ethical relationship to the past demands a refusal of ‘imperial amnesia’; the forgetting of the costs that make a nation or an empire possible. In remembering past injustices, we invite you to consider the value of archival materials in asserting more ethical relationships to the past, present, and future. We invite you to question: How can archival materials expand our understandings of anti-Muslim violence in Canada? What can words, images and objects tell us about how Muslim people responded to anti-Muslim violence? And what role can the archives play in better practicing justice?

Reflecting on systemic Islamophobia, Syed Adnan Hussain contends that an ethical relationship to the past demands a refusal of ‘imperial amnesia’; the forgetting of the costs that make a nation or an empire possible. In remembering past injustices, we invite you to consider the value of archival materials in asserting more ethical relationships to the past, present, and future. We invite you to question: How can archival materials expand our understandings of anti-Muslim violence in Canada? What can words, images and objects tell us about how Muslim people responded to anti-Muslim violence? And what role can the archives play in better practicing justice?

Further explore our database of digitized archival materials.